Agricultural Ignorance and Apathy

by George Powell

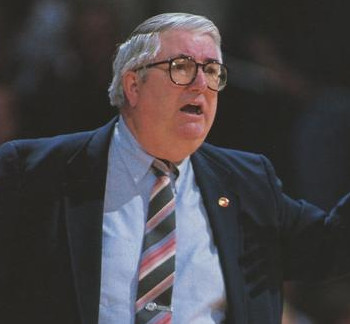

Frank Layden, former coach of the NBA’s Utah Jazz, once recounted a conversation he had with an underperforming player.

I told him, ‘Son, what is it with you? Is it ignorance or apathy?’ He said, ‘Coach, I don’t know, and I don’t care’.

Los Angeles Times, December 10, 1988

And it is the two-headed monster of public ignorance and apathy that creates one of the greatest challenges to agriculture. And, indeed, also for society.

Recently agriculture has been prominent in the news. And rightly so. It is foundational to human health and survival. It is woven into many of our most pressing environmental and socio-economic issues. Yet, move beyond the recent concerns about food inflation and grocery store supply disruptions and very few people seem to care about the viability of Canadian agriculture. Indeed in last fall’s federal election, neither agriculture nor food directly ranked among the top ten voter issues.

So, how do we develop a long-term, supportive public policy for sustainable agriculture? Especially when the majority of the public knows very little about the subject and doesn’t care to learn?

Roots of the Problem

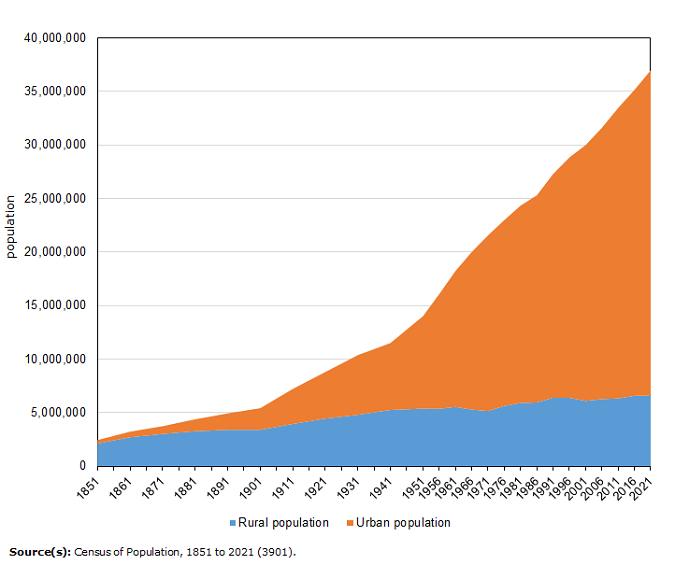

To understand the roots of the apathy, you have to delve into the psyche of western societies. The past five centuries have been marked by a steady of procession of globalization: expansion, industrialization and urbanization. Canada’s recently released 2021 population statistics demonstrate this trend. Roughly 85 percent of the country now lives in urban centres. And this number increases every year.

And through the generations, most urban people have developed an attitude of superiorty through majority. Even if subconsciencely, most people equate moving away from life on the land to progress. And by extension, agriculture is not important because it is primarily not urban.

Without the lived experience of working the land, most people don’t recognize agriculture as an interface between humanity and the planet. As such, farming and ranching has been devalued over time. And as a consequence most people can only relate to agriculture through one of its outputs: food.

Governments and institutions increasingly reflect this limited connection to agriculture. It’s found in the language they use. Governments favour supporting ‘food hubs’ over of agriculture centres. Universities rebrand faculties of agriculture to ‘food systems’.

This is not to suggest that food is unimportant. But when you value products more than the processes that create and sustain them, you become divorced from the real connections of humans to ecosystems. And the ‘I want cheap food and convenient access’ trumps supporting agriculture as a form of applied ecology. Therefore, this attitude obscures agriculture’s links to human health, wealth and survival.

Lack of Engagement

At best, public indifference means farmers don’t have to contend with deep, time consuming policy debates. They can engage directly with the policy makers and hope they understand the issues experienced at the farm level. At worst, one must battle with shallow knowledge that is easily swayed by a meme-driven, sound-byte culture.

The mental distinction between food and agriculture also leads to the public as not seeing themselves as being directly part of agricultural issues. For example, more than 30 percent of food gets wasted at the retail and consumer levels. This waste is more impactful on greenhouse gas emissions, water use and displacement of habitats than any individual agricultural practice. Yet few people tipping their left-overs into the trash see themselves as at the heart of agriculture’s environmental impacts.

Shallow thinking is also reflected in the hypocrisy of over-regulating and restricting local agriculture on ‘environmental grounds’. All the while, importing food from elsewhere. This is tantamount to outsourcing the environmental impacts of your food. And it limits the ability to work collaboratively on solving some of the most challenging agri-environmental issues.

Solutions

In crisis there is always opportunity. And the present abundance of climate-driven crises serve up an opportunity to re-engage the public in a deeper level of understanding and connection to agricultural issues.

It is important to understand that advancing this discussion is a process, and not a one-time event. Indeed, the rural-urban divide is not new, but it has widened with the parabolic urban population growth. Bridging the divide will not be a short-term endeavor.

The solutions start with youth. Support and expand the highly successful ‘Agriculture in the Classroom‘ programs.

Education of adults is also key. Expand opportunities for consumers to speak with producers at farmers’ markets and retail outlets.

Encourging people to grow some of their own food also, even if the volume generated is symbolic, creates real connections to agriculture. Community gardens and forest gardens are important outlets for this activity.

And, educate politicians and policy makers until there is broader societal understanding. They should be a bridge between the huge urban element and the rural minority. Farmers and ranchers simply no longer have the voting power to keep agricultural issues in the mainstream. But democracy does not need to be a tyranny of the majority.

Subscribe via RSS